I wrote this review some while ago now, having not long before finished Andrew Roberts 800 page Napoleon The Great. After that I wanted something that would continue my Napoleonic jag, but wouldn't be quite such a demanding investment in time. Having read Napoleon's own early writing effort, Clisson & Eugénie, in about 10 mins [1], Brendan Simms' The Longest Afternoon turned out to be just what I was after.

Subtitled 'The 400 Men Who Decided The Battle Of Waterloo', it sounds at first a little like it might be trying to re-tell this oft-covered story in the style of what is now termed 'revisionist' history: 'You thought you knew the story? Let me tell you what really happened!' That kind of deal. 2015 is bound to see many new books on the subject, as well as old books recycled or reissued, and in the effort to be noticed a dramatic title could help attract sales and interest. A potentially good example of this kind of attention-grabbing idea is a book I haven't read as yet, entitled The Lie At The Heart Of Waterloo!

Simms also references the works of Peter Hofschröer several times - Hofschröer is well known in Napoleonic circles, partly for his rather confrontational and controversial stance on one issue very relevant here, his position being succinctly summed up in one of his own titles, Waterloo The German Victory - and his (Simms, that is) choice to call his last chapter 'Legacy: a 'German Victory'?' might appear to strengthen this apparent link.

I'm part way through reading the above-mentioned Hofschröer title, so my verdict isn't in on that just yet. But I have to say I really loved his book Wellington's Smallest Victory, which tells the fascinating story of Capt. Siborne's travails in the course of building his famous Waterloo diorama.

La Haye Sainte as pictured on a postcard about a century after the battle.

Actually, although Simms addresses a few areas that have been seen by some interested in Waterloo as difficult or contentious, if not necessarily controversies, I certainly don't think he's really intending to start any arguments, or even stoke the fires of such as already exist. But he does make the point, and very well, that perhaps the action at La Haye Sainte, and in particular the role of the King's German Legion in it, hasn't received the attention their part of the story deserves.

With the approaching bicentennial of Waterloo (it was December 2014 when I originally wrote this) the already gargantuan field that is Waterloo literature is only set to get more crowded, and finding interesting angles on the whole shebang becomes more important for both authors and readers. Simms has done a great job in this respect, focussing on the actions at and around La Haye Sainte, a key feature of the battle of Waterloo. The buildings that comprise La Haye Sainte are described thus on Wikipedia: 'a walled farmhouse compound at the foot of an escarpment on the Charleroi-Brussels road'.

One of several key forward positions in Wellington's defensive line, situated centrally between the other two exposed bastions of Hougoumont and Papelotte, it proved to be a small but crucial stronghold in this most famous of battles, absorbing Napoleon's troops in a manner he'd hoped and planned to avoid. Simms' sources are diverse, and woven well into his account, and his writing style is obviously erudite, but also fluent and easy. He certainly isn't stuffily over-academic; it's not often you see a book by a Cambridge academic on Waterloo quoting Abba under a chapter heading!

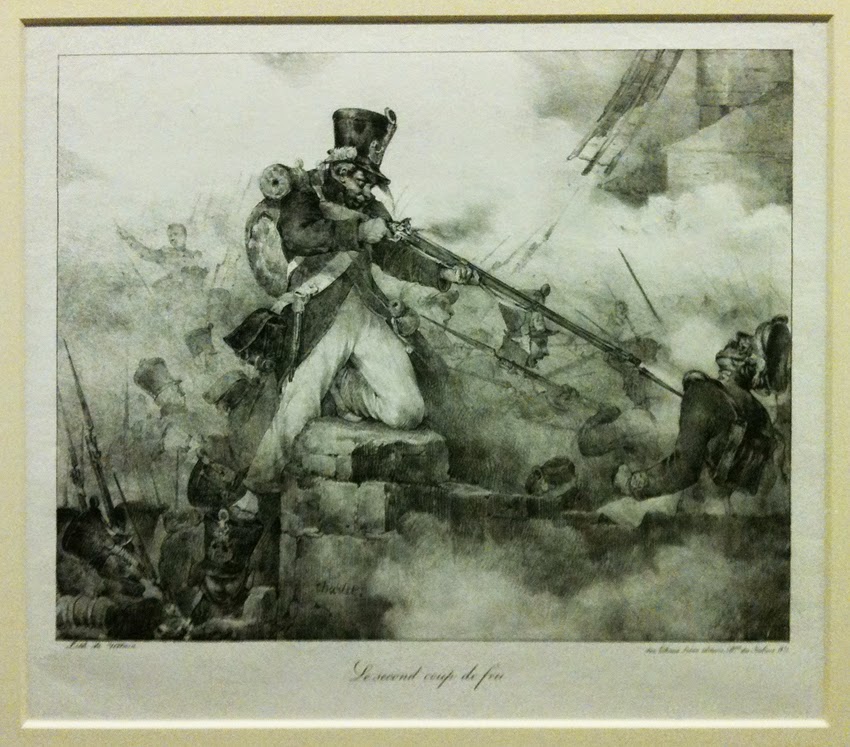

A nice C19th print: Centre of The British Army, at La Haye Sainte.

Another populist reference - and I'm not someone who needs or even wants my history leavened with such things, unless they're pertinent, as they are here - is to the Waterloo episode of the TV series Sharpe, which he notes because it features La Haye Sainte heavily, even portraying Major Baring, who comes as close to a hero as you'll find in Simms' account.

Sergei Bondarchuk's incredible Waterloo movie also depicts some of the action involving La Haye Sainte. In this epic film, although it isn't so central to the film's action as it is in Sharpe's Waterloo, it's certainly portrayed as central to the battle, a fact made abundantly clear when Rod Steiger as Napoleon says 'La Haye Sainte, the one who wins the farmhouse wins the battle'. One of the potentially contentious ideas attached to this subject is whether or not Wellington underestimated the strategic importance of this point of the battlefield, and in doing so risked losing the fight.

The Longest Afternoon is divided into eight chapters, with a short preface, appendices, bibliography and notes. The graphic elements of the edition I have, pictured at the very top of this review, include the cover, a near isometric view of the farm complex used as endpapers, and three maps (La Haye Sainte, the battlefield, and a strategic view of Frech and Allied deployments in Western Europe, in May, 1815). These are all done in a bold linear graphic style that very much resembles old-fashioned woodcuts.

Although this visual style is beautiful, adding to the attractiveness of this particular edition of the book, the maps aren't the greatest I've ever seen, in terms of conveying detail and information. And uniform buffs - and we all know the Napoleonic breed are particulalry tetchy - may find this cover (some editions feature a fantastic oil painting of a scene inside the farmhouse courtyard, as shown below) has some oddities about it. These graphics are by artist and anarchist Clifford Harper [2], a regular contributor of illustrations to the Guardian, amongst other things, who sounds most intriguing!

I think this may be the cover for the US edition. It's a small detail of a much larger (and excellent) painting by Adolf Northern, which I reproduce in full below.

Simms avoids giving too much in the way of time-specific details, and after the main body of the text discusses his reasons, which boil down more or less to the ol' 'fog of war' chestnut. He also notes, after citing numerous personal accounts, that we must be cautious in being too trusting of personal memoirs and the like. Perhaps rather like Wellington on the day of battle itself, Simms uses his materials very adroitly, weaving a very colourful, believable, and engaging portrayal of the events depicted.

I won't go into a blow by blow account of the action - buy and read the book for that, Simms does it very well! - but I will say that I thoroughly enjoyed it. Simms himself has high praise for Barbero's The Battle, and I agree with him, certainly that's the most compelling account of the whole battle of Waterloo I've read so far. Simms' short and masterfully executed work offers something refreshingly different, giving us a window onto a small but crucial aspect of this fascinating and horrifying battle. His contribution to this crowded field is terrific, and a real joy to read.

Adolf Northern: Die Verteidigung des Meierhofes La Haye Sainte bei Waterloo, 1815.

-----

I don't know if this is amongst the Waterloo dioramas I've already covered elsewhere on this blog, but, whilst researching the topic of La Haye Sainte for this post I found this:

The defence of La Haye Sainte ... which looks terrific!

-----

[1] Only 18 of the 128 pages of Clisson & Eugénie are the story itself! most of the Gallic Edition being given over to commentary either side of the rather slight text.

[2] The link in the main body is to a Wikipedia entry on Harper. To visit his own website, click here.